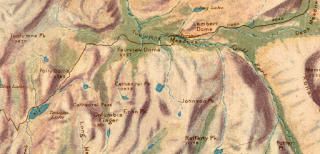

Tioga Pass can be seen as "McLanes Pass" on the 1868 California Geological Survey Map of the Sierra Nevada Mountains near the vicinity of Yosemite Valley.

1868 California Geoloical Survey Map

The mines at Tioga Ridge were initially accessible by way of trails through Lundy Canyon and Bloody Pass. The "Great Sierra Wagon Road" was proposed by the Great Sierra Company which had an estimated cost of $17,000 dollars in 1881 to construct a road from the Big Oak Flat Road near Crane Flat east to the Tioga Peak mines. In 1882 the Great Sierra Company authorized a survey for a wagon road and railroad to the mines of Tioga Ridge which was completed by August during said year. In July of 1882 the California & Yosemite Short Line Railroad was incorporated with the intended goal of also building a rail line to the Tioga Mining District.

By September of 1883 the Great Sierra Wagon Road had been completed east from the Big Oak Flat Road to the Tioga Mining District. The Great Sierra Wagon Road never truly saw it's intended traffic load as the Tioga Mining District shuttered operations during mid-year 1884. The Great Sierra Wagon Road was intended to be a tolled facility but there is no records of any money actually being collected. As the years wore on the Great Sierra Wagon Road remained in periodic use but began to fall into disrepair due to a lack of maintenance.

In 1896 an appropriations bill to purchase the Great Sierra Wagon Road was proposed but never gained traction in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1899 the Army was directed by Congress to survey the Great Sierra Wagon Road. The Army determined the Great Sierra Road while in a state of disrepair had been well engineered with an average gradient of 3%. The Yosemite National Park commissioners found that the Great Sierra Wagon Road could be repaired for $2,000 dollars versus the cost of constructing a new highway for an estimated cost of approximately $61,000 dollars. Yosemite National Park thusly formally recommended that the Federal Government acquire the Great Sierra Wagon Road.

The Tioga Pass Road can be seen ending at the Tioga Mining District on the 1906 Norris Peters Map of Yosemite National Park. A trail over Mono Pass can be seen southeast of Tioga Pass.

1906 Norris Peters Map of Yosemite National Park

In 1899 what would become Legislative Route 40 ("LRN 40") was added to the State Highway System. The original definition of what became LRN 40 according to CAhighways.org called for:

"locating and constructing a free wagon road from the Mono Lake Basin to and connecting with a wagon road called the "Tioga Road" and near the "Tioga Mine"

The Department of Public Works first considered building the eastern extension of the Tioga Road to Mono Basin first via an established pack trail over Bloody Pass. By 1902 a new route via Lee Vining Canyon had been selected and construction began. The September 1950 California Highways & Public Works cites that by 1910 construction through Lee Vining Canyon to the Tioga Mine had yet been completed to State standards. A later Division of Highways article cites that LRN 40 east of Tioga Pass was completed during 1910.

September 1950 California Highways & Public Works

In 1911 the Federal Government brought a lawsuit against the franchise holders of the Great Sierra Wagon (referred to as the "Old Tioga Road"). The Federal suit argued that the Tioga Road had been long abandoned and sought to condemn the franchise rights so it could be incorporated as a Park Road. Ultimately the law suit found that the owners of the Tioga Road had maintained it enough that their claims to ownership were valid.

The completed Tioga Pass Road can be seen in detail on the 1914 USGS Map of Yosemite National Park.

1914 USGS Map of Yosemite National Park

The concept of the Federal Government acquiring the Tioga Road within Yosemite National Park was not revisited until 1915. Stephen Mather, Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior sought to improve automotive access to Yosemite National Park. Mather learned that the purchase price of the Tioga Road within Yosemite National Park was $15,500 dollars. Mather along with several other private contributors purchased the Tioga Road within Yosemite National Park. The Tioga Road was subsequently purchased from Mather's group by the Federal Government for $10 dollars on April 10th, 1915. The Tioga Pass Road was repaired and was opened to automotive traffic on July 28th, 1915. The first year the Tioga Pass Road was opened to traffic only 190 cars entered Yosemite National Park via Tioga Pass.

Much of the above early history of the Tioga Pass Road within Yosemite National Park was cited from Yosemite.ca article on Tioga Pass.

Yosemite.ca on the Tioga Pass Road

According to CAhighways.org in 1915 Legislative Chapter 306 and 396 changed the definition of LRN 40 to include all of the segments Tioga Pass Road and Big Oak Flat Road which were not in within the boundary of Yosemite National Park:

"that portion of the Great Sierra Wagon Road, better known as the Tioga Road, lying without the boundary of Yosemite National Park, providing that the portion within the park is taken over by the federal government." Chapter 396 added "that certain toll road in Tuolumne and Mariposa counties known as the Big Oak Flat and Yosemite Toll Road beginning at a point near the former location of Jack Bell Sawmill in Tuolumne Cty and extending thence in an E-ly direction through a portion of Mariposa Cty at Hamilton Station, thence again into Tuolumne Cty, past the Hearden Ranch, Crocker Station, Crane Flat, and Gin Flat to the boundary line of the original Yosemite Grant near Cascade Creek"

More on LRN 40 can be found on CAhighways.org:

CAhighways.org on Legislative Route 40

On November 11th, 1926 the US Route System was approved by the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture. The US Route System was intended to standardize corridors of national importance into a numeric grid intended to ease cross-country navigation. Changes and additions to the US Route System were put under the governance of the American Association of State Highway Officials ("AASHO"). The initial run of US Routes approved by the California Highway Commission can seen in the January 1926 California Highways & Public Works.

The initial run of Sign State Routes were announced in the August 1934 California Highways and Public Works. CA 120 was announced as a new Sign State Route originating at US 99/LRN 4 in Manteca. CA 120 as originally defined followed LRN 66 east to Oakdale, LRN 13 east to Yosemite Junction near Chinese Camp, LRN 40 to the Yosemite National Park boundary, the Tioga Pass Road through Yosemite National Park and LRN 40 via Mono Mills to CA 168 at Benton near the Nevada State Line.

As noted in the intro a June 1935 sketch map from the Division of Highways shows US 6 with two proposed alignments in California. The first alignment shows US 6 entering California via CA 168 near Benton. US 6 is shown terminating to the south at Long Beach by way of Owens Valley and Los Angeles. The Benton-Long Beach proposed alignment of US 6 was a violation of it's even numbering which was intended to denote a US Route with a cardinal east/west orientation.

The proposed alignment of US 6 to San Francisco via Tioga Pass would have maintained its east/west orientation. The Tioga Pass-San Francisco alignment of US 6 is shown entering California via CA 168 to Benton, all of CA 120 west to US 50, US 50/LRN 5 over Altamont Pass to Hayward, LRN 105 from Hayward to the original 1929 San Mateo-Hayward Bridge, west over San Francisco Bay via the 1929 San Mateo-Hayward Bridge and north via multiplex of US 101/LRN 2 into downtown San Francisco.

A letter dated February 8th, 1937 by the AASHO Executive Secretary to the State Highway Engineers of; Colorado, Nevada and California announced the approved extension of US 6 from Greeley, Colorado to Long Beach, California.

On September 17th, 1937 the Secretary of the Merced Chamber of Commerce sent a letter to the Bureau of Public Roads inquiring about the status of the proposal to extend US 6 to San Francisco via Tioga Pass.

The Secretary of the Merced Chamber of Commerce in a October 2nd, 1937 sent a letter to the AASHO Executive Secretary proposing to add a alternative corridor to US 6 ("US 6A") which would terminate in San Francisco via Tioga Pass. The Merced Chamber of Commerce requested the proposed US 6A depart from Yosemite National Park via CA 140 via the Yosemite-All Year Highway (completed between Mariposa and El Portal during July 1926) which would have it pass through the City of Merced. The Merced Chamber of Commerce proposal cited a continuation of US 6A westward via CA 152 (it is unclear how US 6A would get to CA 152) over Pacheco Pass and US 101 into San Francisco.

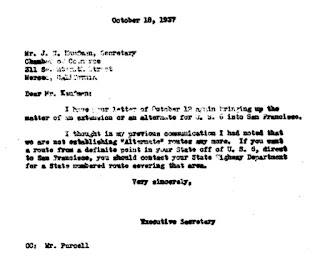

The AASHO Executive Secretary on October 8th, 1937 noted in a reply to the Merced Chamber of Commerce Secretary that US 6 was already approved to be extended to Long Beach.

The Merced Chamber of Commerce Secretary replied to the AASHO Executive Secretary on October 12th, 1937 asking the AASHO Executive Committee to take up the concept of US 6A to San Francisco via Tioga Pass for consideration. The Merced Chamber of Commerce stated an argument that the Tioga Pass Road of Yosemite National Park carried enough merit to be promoted by the US Route System for the proposes of tourism.

The AASHO Executive Secretary noted in a October 18th, 1937 reply the Merced Chamber of Commerce Secretary that alternate US Routes were no longer being considered by the AASHO Executive Committee. The AASHO Executive Secretary did not fully dismiss the concept of a US Route over Tioga Pass and directed the Merced Chamber of Commerce Secretary to work with the California Division of Highways in creating a formal proposal. It is appears that the Merced Chamber of Commerce did not pursue a US Route over Tioga Pass beyond October 1937. Amusingly the the AASHO Executive Committee in the following years would go on to approve numerous alternative US Routes throughout the United States.

Comments