Located about 20 miles west of (or

about 30 miles upriver from) downtown New Orleans, the Bonnet Carré Control

Structure & Spillway is one of three large-scale flood control structures

on the lower Mississippi River designed to regulate the flow of water in the

river in the event of flooding. The other two structures, the Morganza Control

Structure and the Old River Control Structure, are located upriver from Baton

Rouge and were constructed in the 1950s and 60s, significantly later than the

construction that took place at this location in the early 1930s. The spillway here is designed so that the excess water that is diverted will flow directly into the southwestern reaches of Lake Pontchartrain and away from the populated areas of southeast Louisiana in the event of flood-stage river levels.

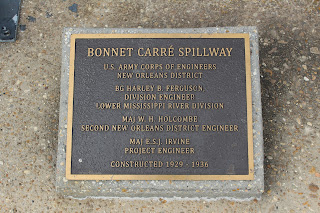

In the aftermath of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the

United States government passed the Flood Control of 1928, which gave the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers the authority to design, construct, and maintain a

flood protection system for the lower Mississippi River and allocated federal

funding for the large-scale undertaking. The levees along the river at New

Orleans are generally not designed to deal with unusually high river levels and

flow rates and the Bonnet Carré Spillway was conceived

as a way to relieve flood-stage water levels in the river and divert the excess

water safely away from the levees around New Orleans as part of the overall flood

protection plan for southeast Louisiana. This was the first large-scale control

structure and spillway project associated with this effort to modernize and rebuild

the levee system in the part of Louisiana in the aftermath of the Great Flood and

it was built shortly after this disaster, becoming operational in 1931.

Of the major spillways on the lower Mississippi River, this

is the one that gets utilized the most often. Since its completion, the Bonnet Carré Spillway has been opened 15 times, most recently

in 2020. The Control Structure itself is built of reinforced concrete

and is about 7,700 ft long and contains 350 individual bays that can be opened to

allow a maximum flow rate of 250,000 cubic feet per second. That volume is

roughly the equivalent of three Olympic-sized swimming pools for every second

that passes. Each of the control structure’s bays contain treated timber gates or

“needles” as they’re known, that can be lifted through the top of the structure

by rail-mounted gantry cranes to enable the passage of water into the spillway.

The total of 7,000 of these “needles” can be removed in as little as 36 hours,

however the spillway has not had to be opened to carry 100% of its maximum flow

rate since 1983. (By comparison, the spillway opening in 2020 opened 90 of the

structure’s 350 bays, resulting in a flow that was about 36% of its maximum

capacity.)

The spillway itself is about six miles long between the

Mississippi River inlet and the Lake Pontchartrain outlet. It varies in width

along its length, ranging from about 1 ½ miles wide near its inlet to about 2 ½

miles wide near its outlet. During times

when the spillway is not in use, the land contained within is used as a

recreation area open to the public. There are four bridges that span the

spillway – two of them are for road traffic and two of them are for railroad

traffic. US Highway 61 (Airline Highway) crosses the spillway closer to the

Mississippi River, while the Interstate 10 causeway bridge is located near the

spillway’s outlet on Lake Pontchartrain.

The following pictures from my visit to the Bonnet Carré Control Structure & Spillway in February 2024 showcase the views of the Mississippi River, the Control Structure, and the Spillway itself from the levee on the west side of the complex. Click on each photo to see a larger version.

The following pictures from my visit to the Bonnet Carré Control Structure & Spillway in February 2024 showcase the views of the Mississippi River, the Control Structure, and the Spillway itself from the levee on the east side of the complex. Click on each photo to see a larger version.

How To Get There:

Further Reading:

Bonnet Carre Spillway by John Weeks

Bridges, Crossings, and Structures of the Lower Mississippi River

Next Crossing upriver: Veterans Memorial Bridge (Gramercy, LA)

Next Crossing downriver: Hale Boggs Memorial Bridge (Luling, LA)

Return to the Bridges of the Lower Mississippi River Home Page

__________________________________________________

Comments