California State Route 1 in western San Mateo County traverses the Montara Mountain spur of the Santa Cruz Mountains. In modern times California State Route 1 passes through Montara Mountain via the Tom Lantos Tunnels and the highway is traditionally associated with Devils Slide. Although Devils Slide carries an infamous legacy due it being prone landslides it pales in comparison to the alignment California State Route 1 carried prior to November 1937 over Old Pedro Mountain Road.

Old Pedro Mountain Road opened to traffic in 1915 and is considered one of the first major asphalted highways in California. Old Pedro Mountain Road clambers over a grade from Montara towards Pacifica via the 922-foot-high Saddle Pass. Pictured above an overlook of Old Pedro Mountain Road facing southward towards Montara as it appears today. Pictured below it the same view during June 1937 when it was part of the original alignment of California State Route 1. Today Old Pedro Mountain Road sits abandoned and eroding away as part of a trail within Montara State Beach.

Version History

- Originally published July 25, 2021.

- Updated July 22, 2022.

Part 1; the history of Old Pedro Mountain Road

Prior to Old Pedro Mountain Road travel over Montara Mountain (sometimes referred to as San Pedro Mountain) was difficult. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, a well-established Native American overland trail existed over Montara Mountain.

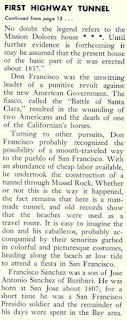

Originally overland travel south of San Francisco towards the Montara Mountain Trail followed the shoreline beaches towards Mussel Rock. During 1874 and early 1875 a highway tunnel was built through Mussel Rock at the behest of Hibernia Bank co-founder Richard Tobin. Tobin desired to be able to travel via stagecoach from his home at Rockaway Beach near the Montara Mountain Trail north to his family's homestead in San Francisco.

The Mussel Rock Tunnel was possibly the first highway tunnel in California, but ultimately proved to be impractical. The Mussel Rock Tunnel was infamous for filling with sand during high tides and never properly functioned as a through highway. The Mussel Rock Tunnel was claimed to be 90 feet in length and was excavated largely via explosives. Ultimately the much of the Mussell Rock Tunnel and approach roads were destroyed during the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. The Mussell Rock Tunnel is sometimes referred to as "Tobin's Folly."

The May/June 1956 California Highways & Public Works featured the Mussel Rock Tunnel. At the time much of the history of the Mussel Rock Tunnel was unclear and it was thought to have been constructed during the 1830s as part of Mexican Rancho San Pedro. A more accurate history of the Mussel Rock Tunnel can be found in the 2010 San Francisco State University document titled Living on the edge: History at Mussel Rock, Daly City, California.

The Mussel Rock Tunnel and Montara Mountain Trail were replaced in 1879 when San Mateo County completed the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road. The Half Moon Bay-Colma Road was built largely west of Old San Pedro Mountain Road above the modern Tom Lantos Tunnels. The general path of the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road can be seen traversing Montara Mountain on the 1882 Bancroft's Map of California and Nevada.

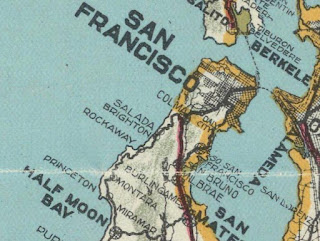

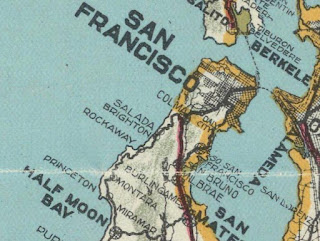

During the early 20th Century, the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road reportedly was incredibly difficult for early automobiles to traverse as it was extremely narrow and featured grades as high as 25%. The Half Moon Bay-Colma Road can be seen in greater detail between Montara north towards Rockaway Beach (now in Pacifica) on the 1914 C. F. Weber & Company Map of San Mateo County.

San Mateo County seeing a need for a better road over Montara Mountain completed what was then known as "Coastside Highway" (now Old Pedro Mountain Road) by 1915 as a replacement for the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road. Coastside Highway traversed Montara Mountain via the 922-foot-high Saddle Pass via a modernized roadway. Coastline Highway carried a gentler 5% average grade which made it far easier for the average car to traverse compared to the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road. Coastline Highway was one of the first asphalted roadways in California.

This photo from the Barbara Vanderwerfs book titled "Montara Mountain" shows a car atop the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road in 1913.

This map hosted on coastsidebuzz.com features a USGS Map sourced from Ken Lajoie (according to Mike Buncic) showing where the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road (Green) is relative to Old Pedro Mountain Road (Red).

Old Pedro Mountain Road can be seen between Montara and Rockaway Beach on the

1917 California State Automobile Association.

During 1933

Legislative Route Number 56 (LRN 56) was extended north from Cambria towards Fernbridge and US Route 101. This new definition of LRN 56 carried numerous segments of coastal highway including the existing roadway from Santa Cruz north to San Francisco. Thusly Old Pedro Mountain Road was added to the State Highway System as part of LRN 56. In the

August 1934 California Highways and Public Works Guide the Sign State Routes were announced. California State Route 1 (CA 1) was applied to LRN 56 from Las Cruces northward towards Fernbridge which included Old Pedro Mountain Road between Montara and Rockaway Beach.

CA 1/LRN 56 can be seen traversing Old Pedro Mountain Road on the

1935 Division of Highways Map of San Mateo County. CA 1/LRN 56 can be seen approaching Old Pedro Mountain Road through Farallone City and Montara via; Farallone Boulevard, 4th Street, Audubon Avenue, George Street and Elm Street. CA 1/LRN 56 can be seen entering Rockaway Beach on what is now Higgins Way.

CA 1/LRN 56 between Montara and Rockaway Beach is featured in the

June 1937 California Highways & Public Works. A new alignment of CA 1/LRN 56 through Devils Slide is shown to be in the process of construction. The new alignment of CA 1/LRN 56 through Devils Slide is stated to be 5.903 miles in length compared to the 10.618 miles on existing Old Pedro Mountain Road. Devil's Slide is shown to have 13,821 feet less in curvature and 1,174 less feet in elevation variance compared to Old Pedro Mountain Road.

The

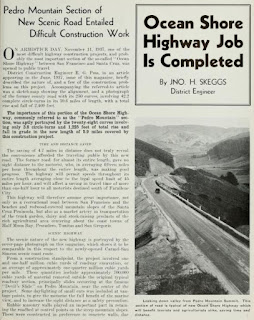

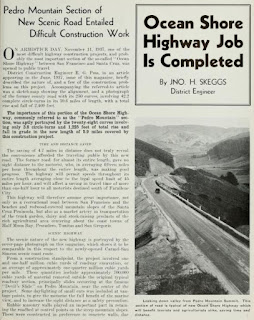

November 1937 California Highways & Public Works features the opening of the new Devils Slide alignment of CA 1/LRN 56 and replacement of Old Pedro Mountain Road. The new alignment of CA 1/LRN 56 through Devils Slide is stated to have opened on November 11th, 1937. Old Pedro Mountain Road is cited in the article to have 250 curves and was generally driven at 15 Miles Per Hour or less.

It is unclear if Old Pedro Mountain Road closed to traffic immediately, but it heavily eroded over time and has long been impassable to automobiles. Old Pedro Mountain Road now exists as a hiking and mountain bike trail within the McNee Ranch annex of Montara State Beach. CA 1 through Devils Slide came to be known for numerous heavy landslides which often closed the highway.

Devil's Slide was replaced in 2014 when CA 1 was realigned through the Tom Lantos Tunnels.

Part 2; a trail run on former California State Route 1 on Old Pedro Mountain Road

Old Pedro Mountain Road can be accessed from a gate located on CA 1 immediately north of Montara at Postmile SM 37.17. The gate closes off vehicle access to North Peak Access Road and acts as a trailhead to Old Pedro Mountain Road. The gate does not have a true parking lot and I found it easier to start my trail run from the Montara State Beach parking lot at Postmile SM 37.04.

The North Peak Access Road trailhead has a map showing where to find Old Pedro Mountain Road.

North Peak Access Road jogs immediately east of CA 1 and intersects Old Pedro Mountain Road.

Turning north on Old Pedro Mountain Road reveals an asphalt surface and an advisory that the trail is multi-use.

Old Pedro Mountain Road begins to climb in elevation and intersects the Gray Whale Cove Trail at the first switchback.

Old Pedro Mountain Road climbs through the first switchback to a curve facing south towards Montara. Point Montara was established as a lighthouse location during 1875 and would see several farmers settle around it during the late 19th Century. In time this collection of farm plots would come to be recognized as the community of Montara. A nearby railroad siding and stop on the Ocean Shore Railroad known as Farallone City was established in 1905 next to Montara. The Ocean Shore Railroad went bankrupt in 1920 but travel on Old Pedro Mountain Road kept the communities of Montara and Farallone City relevant. During the course of the 20th Century the siding name of Farallone City gradually faded and came to be recognized as part of Montara.

Old Pedro Mountain Road continues generally northward through several more switchbacks and picks up the North Peak Access Road.

Old Pedro Mountain Road carries the North Peak Access Road northward to a clearing above Montara where they interest the opposite end of the Grey Whale Cove Trail.

Looking west from the Gray Whale Cove Trail junction reveals a view of Devils Slide and the remains of the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road grade on the mountain side.

Old Pedro Mountain Road continues to climb uphill and splits from North Peak Access Road.

A view of Old Pedro Mountain Road looking south from the split with North Peak Access Road.

Old Pedro Mountain Road beyond North Peak Access Road is far more weathered than it was closer to Montara. Saddle Pass can be seen by looking northeast on Old Pedro Mountain Road.

A look northwest towards Devils Slide and the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road.

Old Pedro Mountain Road loops through the overgrowth and briefly reconnects with North Peak Access Road.

The modern view of Old Pedro Mountain Road as seen from the final junction with North Peak Access Road.

The same view as seen in the June 1937 California Highways & Public Works.

Along with the same view from the earlier undated photo.

The final climb on Old Pedro Mountain Road is heavily overgrown and appears to have been hit with numerous landslides.

A view from Old Pedro Mountain Road westward towards the faint remains of the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road grade.

For comparison the Half Moon Bay-Colma Road grade as seen in the 1913 photo from the book Montara Mountain.

The final climb to Saddle Pass winds through the overgrown on Old Pedro Mountain Road to a trail marker with directions to Montara and Pacifica.

The view northward from Saddle Pass towards Pacifica and the Golden Gate of San Francisco Bay. Pacifica incorporated as a City during 1957 which includes the annexed Rockaway Beach. Old Pedro Mountain Road continues northward towards Pacifica and emerges onto Higgins Way.

An assortment of views descending Old Pedro Mountain Road towards Montara from Saddle Pass. The relatively flat grade of Old Pedro Mountain Road was not difficult for a run and was an approximately 7 mile loop from the Montara State Beach parking lot.

Comments