The 1968 Federal-Aid Highway Act expanded the Interstate Highway system an additional 1,500 miles - increasing the overall network to 42,500 miles. During a series of public hearings and correspondences, the House Subcommittee on Roads, chaired by Illinois Congressman John Kluczynski, would help craft the legislation that authorized funding and the designation of the new corridors.

On May 15, 1968, Chairman Kluczynski sent a telegram to every state highway/transportation department. His request asked each state to return on their state's additional Interstate Highway needs as soon as possible with the approximate mileage and location. He also asked if they intended to attend sub-committee hearings that were scheduled to begin on May 23.

The individual state's responses varied. A number of states responded with specific corridors and mileages, a number were vague or gave long-winded answers in regard to funding and needs, and others requested very little mileage or in the case of Vermont, none at all.

One of the reasons for the inconsistency of state responses was that the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) was against adding new mileage to the Interstate Highway System. AASHO believed that the new highway act should focus on the completion of the original 41,000-mile system. Followed by the focus on improving the "ABC System" of highways. The ABC System was the country's network of primary, urban, and secondary roads. The sub-committee had a number of hearings discussing the ABC System in early 1968. Further, AASHO was fearful that any additional mileage to the Interstate Highway System would dilute the pool of money available to complete the then 41,000-mile system. (66)

In their response to Chairman Kluczynski, Arizona replied that they had an immediate need for five miles in the Phoenix area; however, "Arizona goes along with the AASHO recommendation that additional mileage not be added to the present 41,000 miles, but that on completion of the present Interstate Highway System, the monies in the trust fund be allocated to the States for improvements to the ABC system." (796) They did add a caveat that if Congress wishes to add to the Interstate System they have "extensive needs" within their ABC system that could be logically added to the Interstate network. Arizona would receive a 4.9-mile addition to the system for the first phase of the Papago Freeway.

Arizona's position was shared by a number of states including California, Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, and Nebraska, among others. Many of those same states still added a wish list of new Interstates in case Congress did authorize new miles.

Some state highlights are as follows:

Alabama:

|

| (795) |

Alabama pushed for the inclusion of the 6 miles of Interstate 210 in Mobile. They included the image at the left in their response. It was their top priority. They also asked for 1) US 78 from Birmingham to Mississippi. (This corridor was not added but would later become I-22.) 2) US 80 from I-85 in Tuskegee eastward to Columbus, GA. 3) A 40-mile loop connection from I-65 through Huntsville. Alabama would be awarded a Huntsville-spur (Interstate 565) at a length of just over 19 miles.

The Mobile request was not formally granted until the 1981 Appropriations Act. The entire 6.25-mile length was not built. The corridor was shortened in 1987 and the highway is now Interstate 165.

Florida:

Florida referred to three proposals that have been on file with the Bureau of Public Roads since 1956. They include 1) Tampa to Miami via Fort Meyers. This would be the extension of Interstate 75 that was granted in the legislation. 2) A 28-mile corridor from Miami to Homestead. 3) The Florida segment of a Montgomery, AL to Interstate 10 highway. This was a 16-mile segment from the AL/FL line to Marianna.

Indiana:

Indiana started on what would become the modern Interstate 69 extension. They requested an extension of Interstate 69 from Indianapolis to I-64 in Evansville. Indiana noted that this would be an excellent highway addition if Kentucky requests to complete the Pennyrile Parkway and extend the I-69 corridor to Interstate 24 near Paducah. Indiana would eventually receive an Evansville spur - Interstate 164. Interstate 164 is now part of I-69 today.

Kentucky:

Kentucky asked for the following: 1) A 6.6-mile spur from Interstate 64 into Ashland. 2) A 9-mile Crosstown Freeway in Lexington 3) Multiple items in Louisville - an upgrade of the Watterson Expressway and also two radial connectors.

Kentucky also addressed Indiana's suggestion that Kentucky join them on the Interstate 69 extension. Kentucky's response was we're already constructing toll roads that will connect Evansville to Interstate 24. Today, the tolls are gone and Interstate 69 is signed along the Pennyrile Parkway. A new bridge over the Ohio River is being constructed near Evansville to connect Interstate 69 between the two states.

Massachusetts:

|

| (804) |

Rhode Island did concur with all three proposals and also included a Hartford to Providence Corridor. That corridor was approved as Interstate 82; however, only portions of it were eventually built including what is now Interstate 384 northeast of Hartford.

Michigan:

|

| (806) |

Mississippi and Oregon:

Within the document, both states included detailed maps of their corridor additions. However, the scan of the minutes and transcripts did not include or incompletely scanned the images. Oregon, while agreeing with AASHO's position, did ask for "...some adjustments and minor additions to make the existing system more workable." (821)

Oregon would receive mileage for the Interstate 505 Portland Connector. However, that was later withdrawn in 1979.

Nevada:

While supporting AASHO's position, Nevada did list the Interstate 70 westward extension from Cove Fort, Utah through the state and into California along US 50. A spur from Interstate 80 from Reno to Carson City (eventual Interstate 580) via US 395. Nevada also suggested a Nevada-Oregon-Idaho Interstate along US 95 north starting from Winnemucca. The Nevada portion would be 74 miles.

New Hampshire:

|

| (810) |

New Hampshire took the opportunity to promote a number of corridors in their response. The state felt that they were "short-changed" in the initial Interstate mileage. New Hampshire included this map (at left) that showed a combination of corridors totaling approximately 350 miles. New Hampshire did not receive any new Interstate mileage in the 1968 Highway Bill.

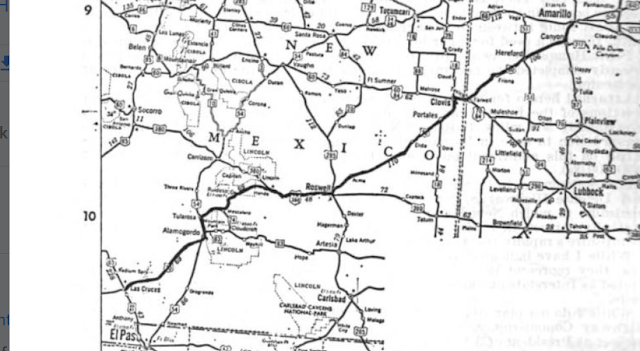

New Mexico:

|

| (812) |

New Mexico reiterated two requests that were made in the mid-1950s and still on file with the Bureau of Public Roads. A 42-mile loop around Albuquerque. And a Las Cruces-to-Amarillo Interstate that followed US 70 from Las Cruces to the Texas State Line and then US 60 and 87 into Amarillo, Texas. New Mexico received no additional Interstate highway miles in the 1968 bill.

North and South Carolina:

Both states did not specifically request any Interstate mileage to the Committee Chairman. However, North Carolina argued for a better share of money from the Highway Trust Fund. South Carolina argued for dedicated funding for upgrading insufficient segments of the current Interstate system. When the Highway Act passed in August 1968, North Carolina received an extension of Interstate 40 from Durham via Raleigh to Interstate 95 in Smithfield. And both states received an extension if Interstate 77 from Charlotte to Columbia.

South Dakota:

|

| (823) |

|

| (824) |

The two urban requests were an east-west loop serving the Sioux Falls Central Business District. The ten-mile Interstate would connect from Interstate 29 and Interstate 229 along most likely West 12th and East 10th Streets.

The second request would be a six-mile inner loop of Rapid City. Interstate 190 would bisect the route at its southern terminus. South Dakota did not receive any additional Interstate mileage.

Tennessee:

Tennessee requested five corridors initially.

- US 78 from Memphis to the Mississippi State Line

- US 51 from Memphis to Fulton, KY at the Purchase Parkway (Part of the Interstate 69 Corridor today.)

- US 23 from the North Carolina line via Johnson City and Kingsport to the Virginia State Line. (Interstate 26 today.)

- US 64 from Interstate 75 in Cleveland to the NC State Line

- US 72 from the Alabama State Line to I-24 near Jasper.

- US 78 from Memphis to the Mississippi State Line (no change)

- Continuation of Interstate 155 from Dyersburg to I-40 in Jackson.

- US 23 from North Carolina to Virginia (no change)

- From I-155 in Dyersburg to Interstate 24 in Clarksville.

- US 72 from the Alabama State Line to Jasper (no change)

Texas:

While Texas did not specifically nominate any corridors, it did note that Lubbock and Wichita Falls were two cities in excess of 100,000 population not having Interstate access. Texas would receive the creation of Interstate 27 from Amarillo to Lubbock and an Interstate 44 extension to Wichita Falls in the 1968 Highway Bill.

But it was two other comments made by Texas that are of interest. The first was their support of AASHO's position, "That if a State or States elect to improve a section of the Primary System to Interstate standards and it would make a logical addition to that System, that it be marked with an Interstate marker." (825) This would eventually become a standard for the Federal Highway Administration's position on adding new Interstates into the system.

Next, Texas argued for rural expressways to be allowed into the Interstate system. They argued that "...some of the severe 'control of access' provisions now required on Interstate construction should be relaxed..." (825) Texas saw this as a way to lessen the cost of the Interstate system by not forcing states to meet the exact standards for inclusion as an Interstate highway.

Wisconsin:

|

| (827) |

Wisconsin requested 10 different corridors totaling just short of 900 miles. The state received the Milwaukee-to-Green Bay portion of their largest request, a 411-mile corridor from Milwaukee to Superior via Green Bay, Wausau, and Hurley. This is Interstate 43 today.

Editor's Note: All page numbers sourced are from: “Hearings, Reports and Prints of the House Committee on Public Works.” Google Books, Google, 12 June 2007.

Sources, Links, and Further Reading:

- “Hearings, Reports, and Prints of the House Committee on Public Works.” Google Books, Google, 12 June 2007, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hearings_Reports_and_Prints_of_the_House/G_E1AAAAIAAJ?hl=en.

- “Highway History.” U.S. Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/highwayhistory/data/page01.cfm.

- Interstate System Add Requests: 1970 ---Scott Oglesby

- Interstate-Guide.com

Comments