Interstate 40 within California is entirely contained to San Bernandio County over a course of 155 miles from Interstate 15 in Barstow east to the Arizona State Line at the Colorado River. Interstate 40 is aligned entirely in the Mojave Desert over the same general corridor established by US Route 66 and the National Old Trails Road. Interstate 40 is known as the Needles Freeway and has an interesting backstory which included the prospect of the Bristol Mountains being excavated by way of nuclear blasts as part of Operation Carryall.

Part 1; the history of Interstate 40 in California

The focus on this blog will be primarily centered around the construction of Interstate 40 ("I-40") within California. That being said the corridor of automotive travel east of Barstow to the Arizona State Line was largely pioneered by the National Old Trails Road ("NOTR"). In April of 1912 the NOTR was organized with the goal of signing a trans-continental highway between Baltimore and Los Angeles. Building a modern road for automotive use through the Mojave Desert of California would prove to be particularly difficult as State Highway Maintenance didn't exist and the general path of travel was alongside the service routes of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad ("ATSF"). The first Auto Trail through the Mojave Desert of California to Cajon Pass was the Santa Fe-Grand Canyon Needles National Highway which was first signed by 1913. NOTR organizers later adopted the routing of the Santa Fe-Grand Canyon Needles National Highway in the western United States by 1914.

The NOTR in the Mojave Desert east of Barstow to the Arizona State Line can be seen in detail on the 1916 NOTR Map.

As part of the 1919 Third State Highway Bond Act the NOTR from Barstow east to Needles became part of Legislative Route Number 58 ("LRN 58"). LRN 58 was extended in 1925 by Legislative Chapter 279 to the Arizona State Line by way of authorization for the California Highway Commission to acquire the right of way to build a highway to State standards. Effectively the NOTR was planned in the early stages of the US Route System to become US Route 60 ("US 60") which can be seen on the

1925 Rand McNally Junior Map of California. Note; US 91 can be seen ending in Bannock at US 60 as it was planned to follow Nevada State Route 5 and the existing Arrowhead Trail.

In the final version of the US Route System which was approved in late 1926 US 60 had become US 66 and US 91 was shifted to the newer Arrowhead Trail alignment through Silver Lake. Early US 66 east of Barstow would follow the same rail frontage roads to the Arizona State Line as the NOTR had. It wasn't until the 1930s that US 66 was fully paved and became the road that is remembered in collective memory today. US 66 can be seen in the Mojave Desert on the

1927 National Map Company Road Map of California.

US 66 of course would become a major corridor of travel as it was the primary US Route connecting Los Angeles to Chicago. In the original version of the Interstate Highway System the route of US 66 from Barstow east to the Arizona State Line was approved as a

chargeable Interstate on July 7th, 1947. Ultimately original version the Interstate Highway System was not legislatively approved.

In the events leading to the 1956 Federal Highway Aid Act the alignment of US 66 east of Barstow to the Arizona State Line was retained as a planned Interstate. This 1955 planning map shows the potential Interstate east of Barstow to the Arizona State Line as a being planned as a two-lane limited access road slated to be complete by 1965.

Ultimately the Federal Highway Aid Act was signed into law on June 29th, 1956. The corridor east of Barstow to the Arizona State Line was given the tentative designation of I-40 when it was approved as a chargeable Interstate during August of 1957. However the California Division of Highways in November of 1957 petitioned the AASHO Executive Committee to change I-40 to I-30. This request was made by the Division of Highways alongside several other Interstate numbering requests in what appears to be an attempt to avoid renumbering numerous US Route and State Highways.

Arizona also requested that I-40 be redesignated as I-30 which can be seen in a December 1957 letter by the AASHO to the Division of Highways.

Ultimately the proposals to renumber I-40 as I-30 were not approved which was one of the many factors that led to the 1964 California State Highway Renumbering.

The J

anuary/February 1958 California Highways & Public Works discusses the opening of a new freeway segment of US 66 south of Needles. This project consisted of the first two lanes of what would become the I-40 freeway towards the Arizona State Line and was opened to traffic on October 15th, 1957.

The

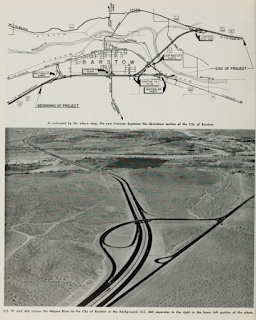

September/October 1961 California Highways & Public Works announced the opening of the Barstow Bypass. The Barstow Bypass was primarily a component of I-15 which opened on July 5th, 1961. The Barstow Bypass included the exit ramp to I-40 and the first stub of the freeway eastward towards Needles.

The

January/February 1962 California Highways & Public Works announced the adoption of 32.8 miles of planned I-40 between Newberry Springs and Ludlow.

US 66/I-40 is cited in the January/February 1962 California Highways & Public Works as having been converted to a four-lane highway through Needles during mid-year 1961.

The

November/December 1963 California Highways & Public Works announced a contract up for bid to construct 9 miles of I-40 southeast of Barstow. The new State Highway budget is cited as helping contribute California's funding to the planned construction of I-40 over the Colorado River at the Arizona State Line.

The

January/February 1964 California Highways & Public Works discusses the prospect of utilizing Operation Carryall to excavate the Bristol Mountains to aid in the construction I-40 east of Ludlow. A feasibility study was jointly submitted by the Division of Highways & ATSF to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission regarding the viability of utilizing controlled nuclear explosions to create a two mile pass in the Bristol Mountains. The Division of Highways and ATSF concluded in their feasibility study that using nuclear devices could be in theory be utilized safely in creating a new route for I-40 and the ATSF freight line. A new pass through the Bristol Mountains was cited as being the ideal route for a shortened ATSF freight line and a straighter route for I-40 to utilize over that of existing US 66. In total a planned 22 nuclear devices totaling 1,730 kilotons of blast force was cited as being needed to make a clean excavation through the Bristol Mountains. Operation Carryall was one of many peaceful purposes for nuclear devices being examined by the Atomic Energy Commission under the umbrella of Project Plowshare.

Further background on Operation Carryall is provided the

Atomic Skies blog page. Operation Carryall was first pursued by the ATSF who wanted to shorten their freight line by 15 miles by way of the Bristol Mountains. The ATSF contacted the Atomic Energy Commission by December 1962 to inquire if this new route could be excavated by way of hydrogen bombs (hence the H-Bomb in the blog title). The California Department of Public Works (which the Division of Highways was part of) joined the ATSF which led to the Operation Carryall feasibility study being submitted to the Atomic Energy Commission during November of 1963. Had Operation Carryall been carried out as planned the new ATSF line would have in theory opened during April of 1969 followed by I-40 during July of 1970. Ultimately the Division of Highways pulled out of Operation Carryall during September of 1966 and the ATSF never built a line through the Bristol Mountains.

This public domain planning map depicts the differences controlled nuclear blasts could make to the new route of the ATSF freight line and I-40.

A close up of the Operation Carryall blast area.

A cross section of I-40 at the bottom of the Operation Carryall blast crater.

The Operation Carryall fallout map.

The

November/December 1965 California Highways & Public Works cites the new I-40 bridge over the Colorado River as presently under construction in California and Arizona. The new Colorado River crossing is cited as having an expected opening during mid-year 1966. The Daggett-Ludlow segment of I-40 is cited as being funded in addition to a segment from Java east to Needles.

The California Highways & Public Works publication ended in 1967 but the

Division of Highways Map from said year illustrates the progress of construction on I-40. I-40 construction progress is shown from Minneola east towards Ludlow. I-40 is shown completed over the Colorado River into Arizona.

I-40 is shown to be completed from Barstow east to the Arizona State Line through Needles on the

1975 Caltrans State Map.

I-40 through the Bristol Mountains was completed in the early 1970s. According to USends.com

US 66 was truncated to US 95 in Needles in 1972 following the completion of I-40 in the Bristol Mountains. This situation would persist with US 66 being multiplexed (at least on AASHO documentation) with I-40 east to the Arizona State Line until at least 1979. Given that the Division of Highways had already sought the removal of US 66 years prior as part of the 1964 State Highway Renumbering there is no clear documentation tracking its truncations through California in the AASHO Database until 1979. In 1979 Arizona Department of Transportation sought and received permission to decommission US 66 from US 95 at Needles through most of Arizona to US 666 in Sanders. The truncation of US 66 from US 95 in Needles to US 666 in Sanders was approved on June 27th, 1979. It is unclear what (if any) US 66 signage California was maintaining at the time the highway was truncated to Sanders.

Part 2; scenes around Interstate 40 in California

In terms of scenery there isn't much to find along I-40 in California (unlike former US 66). Nonetheless I-40 has it's own quirks and interesting features that do stand out. Beginning in Bartsow traffic transitioning from I-15 onto I-40 eastbound is greeted with signage which indicates Wilmington, North Carolina as being 2,554 miles away.

A strange sign on I-15 northbound in Barstow which has I-40 labeled as "Route" followed by a I-40 button-copy shield.

Much of I-40 east from Barstow is designated as San Bernarndino County Route 66. San Bernardino County Route 66 is mostly aligned over former US 66 and is the newest Sign County Route in California which was designated in 1991. Unfortunately much of former US 66 east of Amboy is not accessible following heavy rains washing out bridges during winter of 2017. This sign can be found on National Old Trails Road west of Daggett approaching I-40 Exit 5.

East of Daggett near Newberry Springs off of Exit 18 one can find the Bagdad Cafe of US 66 fame. The Bagdad Cafe is named after a ghost town on US 66 near the Amboy Crater and a movie by the same name from 1987. I-40 Exit 50 accesses the ghost town of Ludlow. Ludlow is where I-40 splits from former US 66 eastward into the Bristol Mountains. Ludlow dates back to 1883 when it was created as a railroad siding along the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad.

I-40 Exit 107 accesses the original alignment of US 66 in Fenner. Fenner was another siding of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad but is more well known for it's RV park and electric generator driven high gas prices. This photo was taken from Fenner in 2012.

I-40 has numerous Exits into the City of Needles. This photo of the El Garces Hotel was taken from I-40 Exit 142 at J Street in Needles.

El Garces Hotel is a Harvey House which serviced rail passengers to Needles which was completed in 1908. Below El Garces Hotel can be seen undergoing renovations in 2012.

I-40 carries a multiplex of US 95 from Exit 133 east through Needles to Exit 144. This sign assembly was located on Needles Highway.

I-40 Exit 153 accesses the former alignments of US 66 and the NOTR near the Arizona State Line at the Colorado River. The ruins of the 1947 Red Rocks Bridge can be found along with converted Old Trails Arch Bridge. The Old Trails Arch Bridge was completed in 1916 and served as part of the NOTR in addition to early US 66. The Old Trails Arch Bridge was retained when the Red Rocks Bridge opened in 1947 and now carries a gas pipeline.

Comments